Graysville Academy is now Southern Missionary College. Its new location is Collegedale, Tennessee. It’s growing, eventually crossing over the threshold of 1,000 students. There are students from all over the country, yet they all have one thing in common:

None of them are Black.

An aged Anna Knight (1874-1972)

The year is 1965. Southern is still segregated. Anna Knight, our Mississippi Girl (from the previous blog post), is still alive and serving her own people at neighboring Oakwood College. The Civil Rights Movement is in full swing. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka passed over a decade prior, yet “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever!” rings true in neighboring Alabama. Southern students also host Civil War-themed events and include the Confederate flag in the gymnasium while donning blackface.

This was a southern Adventist’s new normal.

A bit of backstory:

By the 1950s and 1960s, “conservative ideologies and theologies” leaked into the Adventist Church, discouraging church members from participating in sociopolitical activity. They maintained the walls of separation, quoting Auntie Ellen whenever the questions were raised:

“Let the colored believers be provided with neat, tasteful houses of worship. Let them be shown that this is done not to exclude them from worshiping with white people because they are Black…Let them understand that this plan is to be followed until the Lord shows us a better way.”

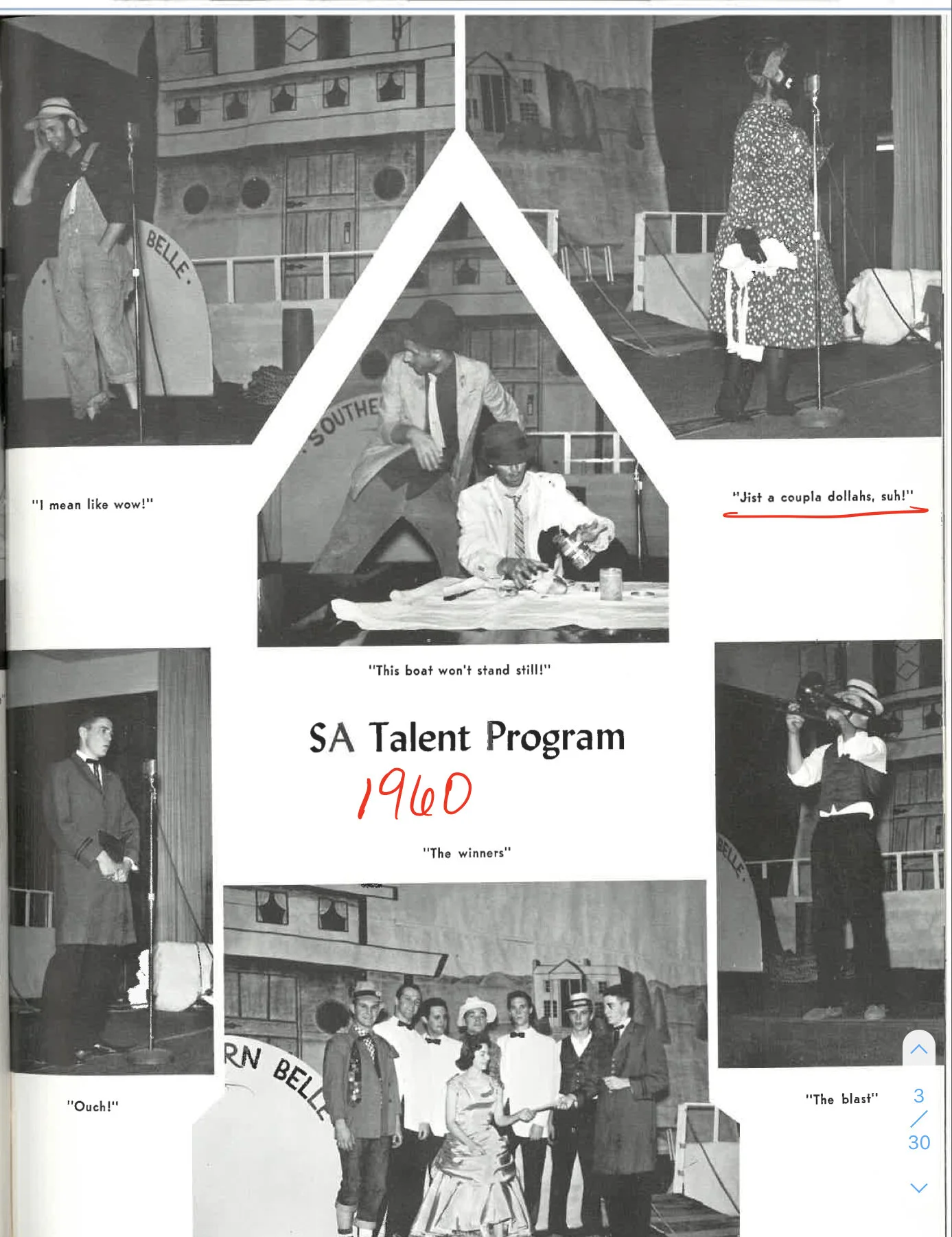

“‘Jiggaboos’ on the loose” [white students in blackface] at a “Band Party” in 1960 at Southern Missionary College

Sounds pretty temporary. Auntie Ellen was advising out of concern for safety, not out of racial bigotry and advocacy for segregation. Often, Ellen was taken out of context. Unfortunately, such quotes were used to tell Black Adventists to stay in their lane. Many white Adventists used her statements to support indifference towards social injustice.

“I am burdened, heavily burdened, for the work among the colored people. The gospel is to be presented to the downtrodden Negro race. But great caution will have to be shown in the efforts put forth for the uplifting of this people. Among the white people in many places there exists a strong prejudice against the Negro race. We may desire to ignore this prejudice, but we cannot do it. If we were to act as if this prejudice did not exist we could not get the light before the white people. We must meet the situation as it is and deal with it wisely and intelligently.”

By 1960, the Student Association of Southern Missionary College held talent shows based on minstrel shows of the late nineteenth century—including the use of blackface and “ebonics” (see top right).

Ellen White recognized that prejudice was growing stronger in the South, especially in a time when both Southern and Oakwood were just emerging. She warned that one might want to ignore this prejudice, but it’s not possible. In the same light, it’s not possible to ignore the plights of the underprivileged around us today. She said it was our duty to meet these situations head-on!

“For many years, I have borne a heavy burden in behalf of the Negro race. My heart has ached as I have seen the feeling against this race growing stronger and still stronger, and as I have seen that many Seventh-day Adventists are apparently unable to understand the necessity for an earnest work being done quickly. Years are passing into eternity with apparently little done to help those who were recently a race of slaves.”

Today, it can be argued that many Seventh-day Adventists refuse to understand those around them that seek their assistance. Instead arguing that “all lives matter,” when their matriarch explicitly said that certain people needed their help:

“The American nation owes a debt of love to the colored race, and God has ordained that they should make restitution for the wrong they have done them in the past. Those who have taken no active part in enforcing slavery upon the colored people are not relieved from the responsibility of making special efforts to remove as far as possible, the sure result of their enslavement.”

In 1962, Southern Missionary College’s gymnastics team made sure to include their “heritage” with routine performances.

Auntie Ellen explicitly said that even those who weren’t slave owners are held accountable. Even if you don’t feel as though you’ve done something personally wrong, it is still up to you to do the right thing. We all have to. Yet for years, in the Seventh-day Adventist Church, especially after Auntie Ellen passed away, her counsel was ignored or taken out of its historical context.

Now, back to the 1960s.

“Since Jesus is coming back soon, all of this will be done away with. There is no need to protest! Stay focused on Jesus!” came the cries of many conservative preachers during this era.

But for many Black Adventists, the time had come. If the United States was desegregating public schools and facilities, then why was the Adventist church and education system (the world’s second largest), still behind on this?

“As was typical, the Seventh-day Adventist Church was not merely guarded in its response to the eras racial tension and disparities; it functioned in strict obedience to the patently discriminatory laws of the land, believing that it should leave issues of civil and social justice exclusively to civic authorities. In consequence, Black Adventists found themselves locked out of worship in white churches, denied admittance to white hospitals and schools, shut out of policy-making/leadership positions within the church structure, and generally embarrassed in the Black community because of Adventism’s radical withdrawal from social protest.”

Regional conferences had been formed after several years of protests by Black Adventists, especially after the death of one Lucille Byard.

Even Oakwood students declared their dreams for representation on campus, in a world where Oakwood had a completely white administration.

“Over time, [white] school administrators erected and maintained social barriers between the black students and the white employees. Segregated dining facilities, racial slurs, and the exclusion of blacks from positions of authority and prestige became commonplace. As an example, in the presence of members of the Oakwood staff, the young son of the junior college president once stretched out his little arm in the direction of the black students working in the field and, with a broad grin, exclaimed: ‘These are all my daddy’s niggers!’”

Oakwood eventually was able to hire an all-Black faculty, staff, and administration. Yet for several decades, the Adventist Church would not budge nor make a statement on segregation. Instead, quotas limited Black people from entering Adventist schools, hospitals, higher education, offices, and more.

Southern, simply, did not allow any Black representation. They wouldn’t even let you eat in the cafeteria if you even made it that far.

E. E. Cleveland (1921-2009)

This is a short story from the early 1950s:

Edward Earl Cleveland, however, was a brave man. A legendary evangelist and church leader, E.E. Cleveland had his own experience with Southern. It’s worth noting that Cleveland was a massive Adventist celebrity amongst his own people, baptizing thousands and becoming a fixture on Oakwood’s campus.

An evangelist for the Southern Union at the time, E.E. Cleveland took part in a committee meeting at Southern Missionary College in Collegedale, Tennessee.

He did the thing most Black people do when they enter a room: he made a mental note of how many other people looked like him. He numbered six other Black people, bringing the total in the room to seven.

V.G. Anderson was the president of the Southern Union at the time. As the clock struck twelve, Elder Anderson announced it was time to head to the cafeteria.

“I don’t know about y’all, but I’m ready to eat!” he called to the constituents as the morning’s meetings concluded.

Well if the president says it, it must be time. I’m rather hungry, anyway, Cleveland thought to himself. He got up and filed into the line.

A hush came over the room.

Cleveland noticed the other six Black people had not yet gotten up from their seats. The man said it’s time to eat! Why aren’t y’all moving? Brother, I know you can throw down on some of this food!

Since Cleveland was a new committee member, he hadn’t yet learned the rules: Negroes, or Coloreds, don’t eat in the Southern Missionary College dining hall.

Cleveland heard the whispers all around him. He got the message.

The president wondered why everyone had gotten quiet. He glanced at Cleveland, a recruit out of Huntsville, Alabama. President Anderson also noticed Cleveland’s darker complexion.

He approached Cleveland, eyebrows knitted and furrowed in frustration.

I ain’t moving, Cleveland seemed to say without saying it aloud.

You really want to do this? Right here? Right now? Anderson tried his best to project his thoughts into Cleveland as they both stared at each other, sternly.

It was as though you could hear everyone’s hearts beating frantically. Thump. Thump. Who would make the first move? Thump. Thump.

Anderson took a breath.

He turned away from Cleveland and addressed the six other Blacks who looked on with blank faces.

“Fine!” Anderson spat. “I guess the rest of you can eat in the dining hall. Get in line.”

It was between 1950-1954 that this stand-off occurred. The first time African Americans dined in the cafeteria at Southern Missionary College [This cafeteria was torn down in 1971 and is not the same cafeteria Southern students dine in, as of 2020].

Time was ticking.

But first, we’ve got to talk about what happened in 1960 and 1961.

“Frank W. Hale Jr., an Adventist layman...visited Adelphian Academy in Holly, Michigan in 1960. Hale sought to obtain information for his daughter, who would soon be of age to attend. In an interview with the school’s dean, Hale received the impression that African American students were not welcome at the institution. The Adventist administrator told him that, out of a student body of three hundred, there were only three blacks. Hale asked if the academy had a quota limiting the number of African American students. The dean replied in the affirmative, and suggested that black students admitted to the institution must come from an upstanding family with a professional background. Hale learned that other Adventist academies had similar policies. He also discovered that blacks were routinely turned away from the denomination’s hospitals, nursing homes, churches, and recreational facilities.”

Frank W. Hale, Jr. (1927-2011)

Frank W. Hale, Jr. became an absolute legend. He strategically created the Laymen’s Leadership Conference (LLC) to correct social injustices in the Adventist church. Together, they identified several causes of racial discord: a lack of interracial dialogue, the bypassing of opportunities to create institutions to improve race relations, abandoning Christian values of love and inclusiveness, catering to the wishes of ultraconservatives, and failure to follow Auntie Ellen’s counsel in The Southern Work.

Clearly, there was a lot to be done.

The LLC demanded the church to take a positive stance on race relations, open institutions of higher education to Black students, discontinue the quota system (white Adventist schools would truly limit the number of Black students), provide equal employment opportunities, cease racial discrimination in its churches, and so much more. Most of all, they demanded that all these things happen as soon as possible.

Shout out to Dr. Samuel G. London, chair of the history department at Oakwood University for all this incredible information.

“[Seventh-day Adventists] did not officially address the issue [segregation] until 1961, making it one of the last of recognized American denominations to publicly declare its position on the matter, following the Presbyterian Church USA (1956), Evangelical United Brethren (1956), United Church of Christ (1956), The Methodist Church (1956), The Church of the Brethren (1956), the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod (1956), American Baptist Convention (1957), American Unitarian Association (1957), Disciples of Christ (1957), The Catholic Church (1958), and the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (1959).”

The General Conference actually heard the LLC and agreed! In October 1961, the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists finally acknowledged that racial segregation was incompatible with Christianity.

It was time to desegregate.

Southern Missionary College, you’re up.

Remember when I mentioned that in 1961, the decision was made to begin integrating?

Well, if you walked onto Southern’s campus in 1962, there’d be no Black students. 1963? No Black students. 1964? No Black students.

But 1965?

There was one man determined to be on the right side of history. I feel that he never gets any credit.

Leroy Leiske (1920-2016)

In 1964, a white man was chosen as president of the Southern Union Conference. The Southern Union includes the Carolina Conference, South Central Conference, South Atlantic Conference, Gulf States Conference, Florida Conference, Southeastern Conference, Georgia-Cumberland Conference, and Kentucky-Tennessee Conference. If you’re a bit confused because that’s a lot of conferences, think of these as anywhere within Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, North and South Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

This white man shocked the southern Adventist world when he became president:

“I intend to integrate everything in this conference,” he told his constituents.

They promptly planned his removal.

Yet, before he left office, this man did something incredible: he desegregated Southern Missionary College. He authorized that nonwhite faculty be hired. He invited Black presidents of the local regional conferences to be voting members of Southern’s Board of Trustees.

His name was Leroy Leiske and after thirteen months as Southern Union president, he was removed from office.

These were Southern’s first steps to integration.

Unfortunately, they and the entire Southern Union were still dragging their feet, even after Leiske’s efforts.

Naturally, the Attorney General of the United States had something to say about it.

Nicholas Katzenbach, the representative from Washington, D.C. who confronted then-segregationist governor George Wallace at the University of Alabama, was a man you didn’t want to hear from.

This is based on the actual interaction as recorded in Dr. Samuel G. London’s Seventh-day Adventists and the Civil Rights Movement:

Nicholas Katzenbach (right) confronts Gov. George Wallace (left) at “The Stand of the Schoolhouse Door” in 1963

“You mean to tell me that you people still practice racial segregation in your facilities a whole decade after Brown v. Board of Education?” I imagine him shouting frantically over the phone at the General Conference. “Fools! You call yourselves a Christian denomination? Let’s get right to the point: You will plan on integrating your facilities, will you not?”

There was silence on the other end of the phone. And it was lengthy.

“I respect that you are a private institution,” he continued. “You do not have to desegregate, but if that is your decision, you will no longer enjoy our assistance. Yes, that includes tax exemptions.”

Nicholas Katzenbach (1922-2012)

“Oh, sir! That certainly won’t be necessary. We just need time, you see. This is all rather so much for us. We just need to call the Alabama-Mississippi Conference [currently the Gulf States Conference] and talk the matter over with them! If you’ll just give us a bit more time, we—“

I imagine Katzenbach cutting straight to business.

“Expect a call from me in exactly two weeks. I’d like to hear progress,” he said, promptly hanging up the phone.

Two weeks passed.

“Oh, sir! You’ll be delighted to know that the Alabama-Mississippi Conference has voted to integrate its schools! Just you wait, pretty soon maybe the rest of—“

“Excellent. It had better be not just Alabama and Mississippi, but for all Adventist facilities, period.”

In its 1965 Spring Council, the General Conference issued a resolution, recommending the immediate desegregation of all denominational facilities and institutions.

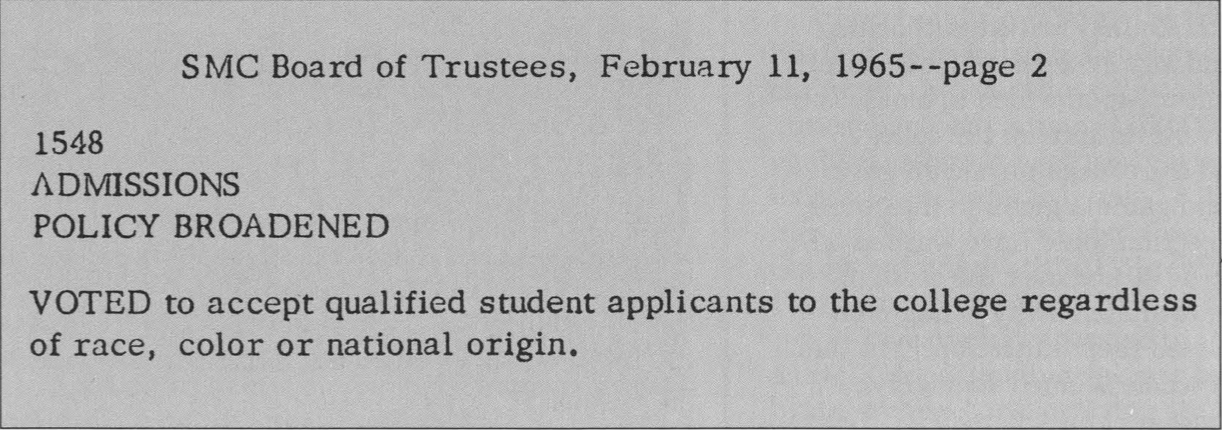

The Southern Missionary College Board of Trustees votes, on February 11th, 1965, to accept students of color.

According to school records, Southern students stood up in chapel and… gave the policy a standing ovation. Both editors-in-chief for the Southern Accent student newspaper in 1965 and 1966 called for viewing the race question as Christians united in an “ideal” colorblind society.

But is that it? Is the story over?

Frank Hale argued that even though the General Conference made a resolution to desegregate Adventist facilities, it was not worth the paper it was written on if it’s not implemented. I believe he was right:

“Integration alone is not enough to bridge the gulf of inequality that still exists within the Seventh-day Adventist Church… This persistent inequality blunts the effectiveness of the church’s witness to the world—that the denomination cannot spread the gospel when there is a continual presence of bitterness, discord, and racism within the organization.”

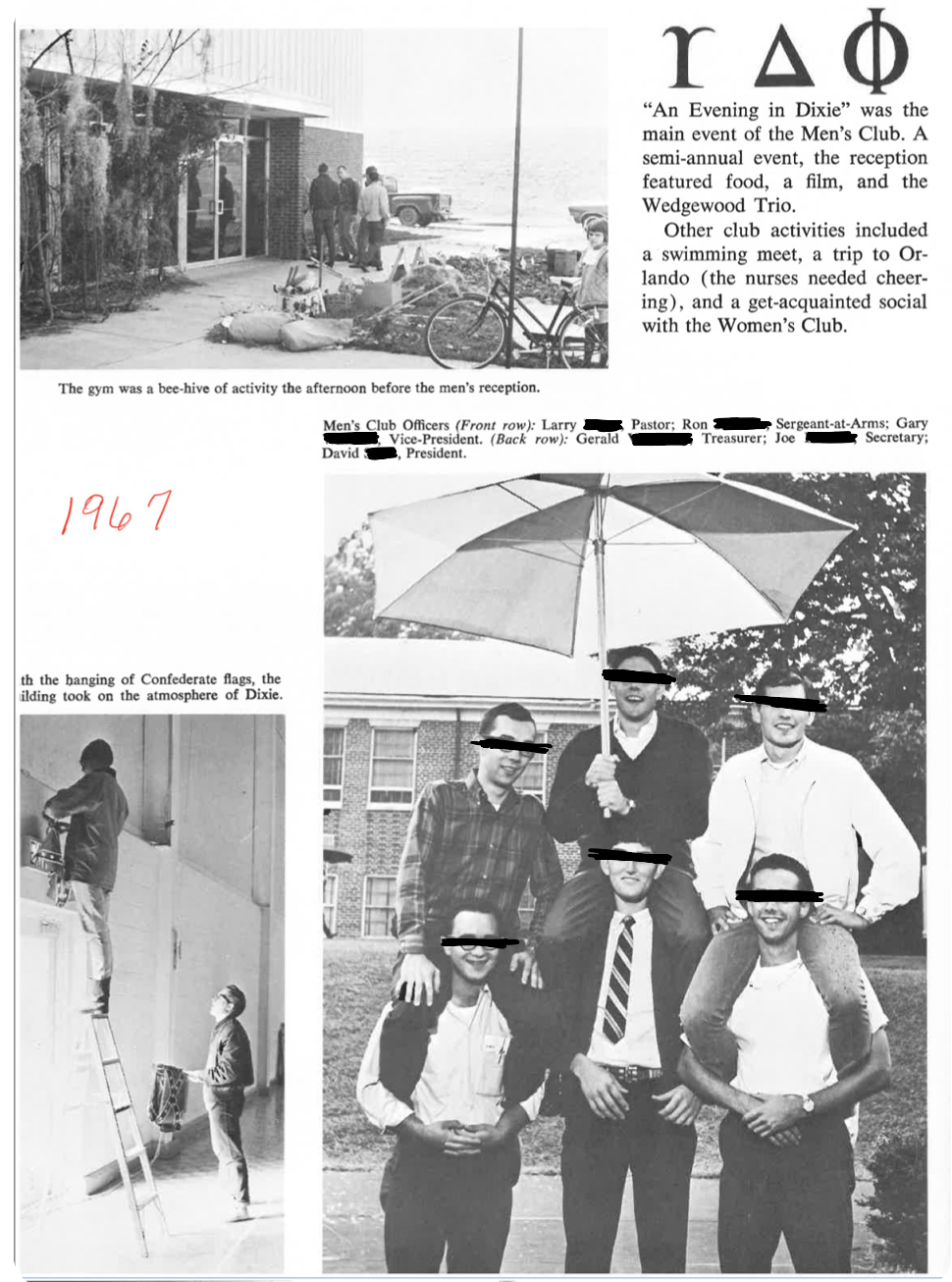

Southern Missionary College in 1967. “An Evening in Dixie” program by Talge Hall will continue for several years, even with Black students on campus.

When Black Adventists like Warren St. Claire Banfield Jr. entered leadership, they began to hear the sentiments from white administrators at Southern Missionary College when Southern began to hire Black faculty:

“You know we wouldn’t have voluntarily integrated this college [Southern]. The Holy Ghost didn’t make us do this. We were not responding to the Holy Spirit. We were responding to political pressure. If the government wouldn’t have threatened to cut off our accreditation, or funding, we would have never integrated this school as soon as we did.” - An anonymous white administrator of Southern Missionary College whom Banfield refused to name, carrying this secret to his grave.

Meanwhile, the Ku Klux Klan monitored Southern’s campus. Sure, you can desegregate, but the local community is watching you. The Klan wanted to make sure that when Oakwood students visited, they remembered who was in charge.

Some students chose, defiantly, to be on the right side of history.

Some Black students chose, in the midst of strife, to attend Southern Missionary College. Annie Beatrice Robinson Brown was the first Black graduate of Southern, and while I cannot find her whereabouts, I will continue to seek out her story. While it has been very difficult to find the stories of the original few Black students, I am happy to have attained at least one from the first female and first Black female Student Association President of Southern: Gale Jones Murphy.

Rollin Mallernee, Southern Missionary College, Student Association President (1967-1968)

Rollin Mallernee, 1967-1968 Student Association President, chose to do the right thing. A young white male, Mallernee also showed courage in the face of potential ridicule. 50 years later, Mallernee shared his story with me by sending me a letter within my final month as Student Association President. His story and the letter he sent me 50 years later, I will tell with permission, in due time.

There were only five Black students in a sea of over 1,000 Southern students in 1968.

While Southern Missionary College began to move in the right direction into the 1970s, there was still so much more to be done. I found that very few Black students who started at Southern would stay there for their four years—some transferred to Oakwood, where they felt celebrated, not tolerated.

Southern even began to celebrate Black History Week, officially adopted a policy for affirmative action in the employment of women and members of minority groups, as well as adopted an official racial nondiscriminatory employment policy.

It was about time.

In the next section of this series, I’ll be sharing the stories of Rollin Mallernee (Student Association President 1967-1968), Southern’s first Black professor in 1975, the first female and first Black Student Association President of Southern in 1974, and some of the Black students who left Southern to attend Oakwood College.

When’s the Continuation?

As I have devoted more of my time towards my Ph.D in United States history, this project is currently on pause as I gather more material, insight, oral histories, and primary resources. I’m not quitting at all, but please be patient as I learn and talk with some of the amazing people who will help this project get off of its feet!

I hope, in the next few years, I’ll be able to write a book, create a documentary, and produce a narrative podcast about this very important subject. For now, most of my interviews and other resources that I’m compiling to tell the Southern story of the last 50+ years will debut in my dissertation in the next few years.

If you have a story that aligns with the racial history of Southern Adventist University, I want to invite you to share your story with me. Even if you’d rather be anonymous, that’s completely okay! I’m especially accessible through Facebook Messenger, Instagram, or my academic email: phillip.warfield@bison.howard.edu.

So, while this won’t be updated for a period of time, I hope that when my research pops up again, you’ll still be interested.

I’m thankful for the 14,000+ of you who have read and shared this project. It was your interest that helped to validate my pursuit of this subject. It’s important to me, and I’m glad it’s important to you as well.

If you’re interested in my other creative work, outside of history and Adventist topics, I invite you to listen to my narrative podcast, check out my blog, and my YouTube channel.

Thanks so much for your ongoing support!

![“‘Jiggaboos’ on the loose” [white students in blackface] at a “Band Party” in 1960 at Southern Missionary College](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b38440150a54fdfbd2dacea/1593993525662-G23B8R4OOYWVJHK0ARNZ/Screen+Shot+2020-07-05+at+7.58.35+PM.png)